Unit 7 Overview: Harmony and Voice Leading IV (Secondary Function)

7 min read•june 18, 2024

Sumi Vora

AP Music Theory 🎶

72 resourcesSee Units

7.1: Tonicization through Secondary Dominant Chords

Oftentimes, music will switch between keys. If the music retains a secondary key for a relatively long time, then that is called modulation. However, if the music only retains the secondary key for a couple of phrases, that is called tonicization. In either scenario, a secondary note will act as the tonic. And, as follows, there will be a secondary note that acts as the dominant, i.e., the secondary dominant.

You can only tonicize major or minor triads–not diminished or augmented triads. That means that in a major key, vii° cannot be tonicized, and in a minor key, ii° cannot be tonicized. In written music, it is easy to identify tonicization when there are accidentals.

It is most common to tonicize to the dominant, the subdominant, or the supertonic (V, IV, ii) of the primary key. For example, in A major, the secondary key would be the dominant–E major–so the secondary dominant would be the dominant of E major–B major. So, if you're looking at a piece in A major and you see II chords popping up, then you may want to consider the idea that you are looking at a secondary dominant.

If you're in a secondary key, then you will notate chords in that secondary key. From the previous example, instead of writing the B major chord as a II chord, you will write it as a V/V chord (i.e., the chord/the scale degree of the "second" chord).

Ex: Let's look at an example. Here is an excerpt from the 2nd movement of Beethoven's Piano Sonata no. 10 in C major

Image via Wikipedia

Measure 17:

- Beat 1: V⁷

- Beat 2: I

- Beat 3: VI⁷ (A-C#-E-G)

- Beat 4: ii (D-F-A)

Looking at beat 3, we see that there are accidentals (C#) and that the VI chord resolves to a ii. Since A is the dominant of D, it is likely that the VI⁷ chord is actually a V⁷/ii chord. So, measure 17 actually looks like: V⁷ - I - V⁷/ii - ii

You'll notice that this progression makes more sense musically. We usually don't see VI⁷ chords in music, and the V⁷-I-V⁷-I progression shows a pattern that we wouldn't have noticed before.

Practice: Try measure 18 and then check your answers with the image below:

Image via Wikipedia

Measure 18 extends the pattern established in measure 17. Beat one has the chord B-D#-F#-A (VII⁷) and beat two has the chord E-B-G (iii). Thus, writing the VII⁷ chord as a V⁷/iii chord that resolves to a iii would make sense.

Note: you can't have a V/IV chord in major; you can only have a V⁷/IV. This is because a V/IV would be a I chord.

How do I know whether it’s a secondary dominant or just a weird chord?

In AP music theory, it is very unlikely that you will see chords that are just...out of place. Here are some questions to ask yourself:

- Are there accidentals? If you find any accidental in a chord, then it's likely that you're dealing with tonicization. There are a few exceptions.

- V/IV in Major: in a major key, you can't have a V/IV because it will just function as a I chord. However, you can have a V⁷/IV.

- V/VI in minor: this is similar to V/IV. It is very uncommon to see V/VI, but you might find V⁷/IV.

- It is also very unlikely to find secondary chords that are not secondary dominants or secondary leading tones. If you see a weird major chord that then resolves to a chord that is a 5th below it/a step above it, chances are, you are looking at a secondary chord.

- HARMONIC CONTEXT IS EVERYTHING! In the example above, there was a clear pattern that had been established: V⁷-I-V⁷-I-V⁷-I. In a secondary key, you will likely see the most common chord progressions in music. If the chord progression in your secondary key doesn't make sense, then it is probably not a tonicization.

- Focus on the function of the chord rather than the chord itself. Is there a cadence? Where is the chord located in the phrase? What chords are surrounding it? All of these questions should help you determine whether you're looking at tonicization.

7.2: Part Writing of Secondary Dominant Chords

Secondary chords follow the same voice leading and doubling rules as any other chord progression. Usually, secondary dominant chords will be written in 1st inversion so that the #4 is on the bottom. A IV-V⁶₅/V-V progression is common because it establishes the bassline 4-#4-5, and a chromatic bassline sounds cool. Additionally, if you see the #4-5 progression, then you can assume that it is a V/V-V progression of some sort.

There is one exception to voice-leading rules for secondary dominants. When you are tonicizing, you will have a new temporary leading tone. Instead of resolving up, that temporary leading tone can resolve down to become the seventh of the next chord.

Harmonic Progressions with Secondary Dominants

You can insert a secondary dominant anywhere in the middle of a chord progression. Let's say that you have a chord progression I-iii-vi-ii-V-I and you wanted to put a secondary dominant before the vi. Then, you would just have I-iii-V/vi-vi-ii-V-I. You can also chain secondary dominants, e.g., I-iii=V/vi-V/ii-V/V-V-I.

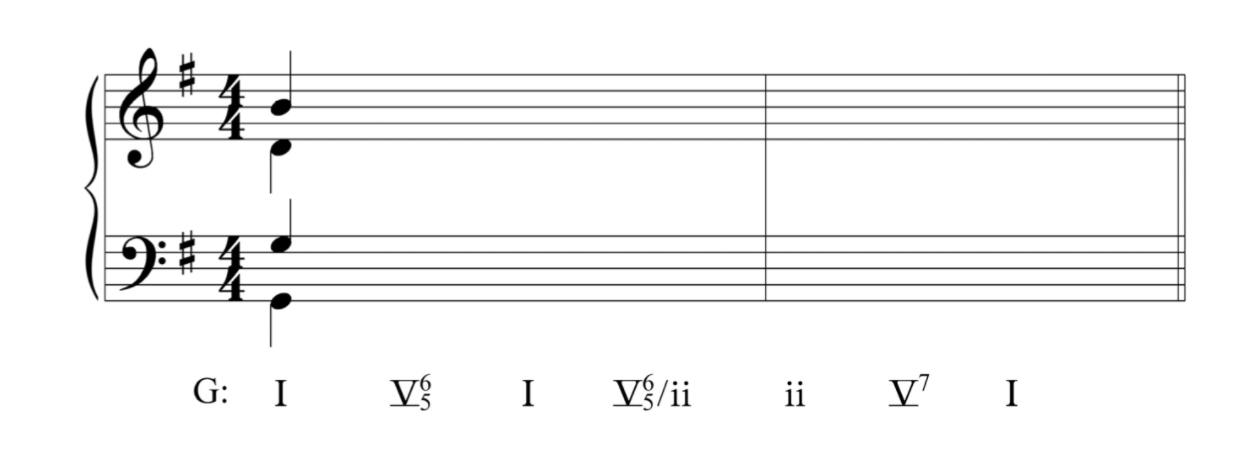

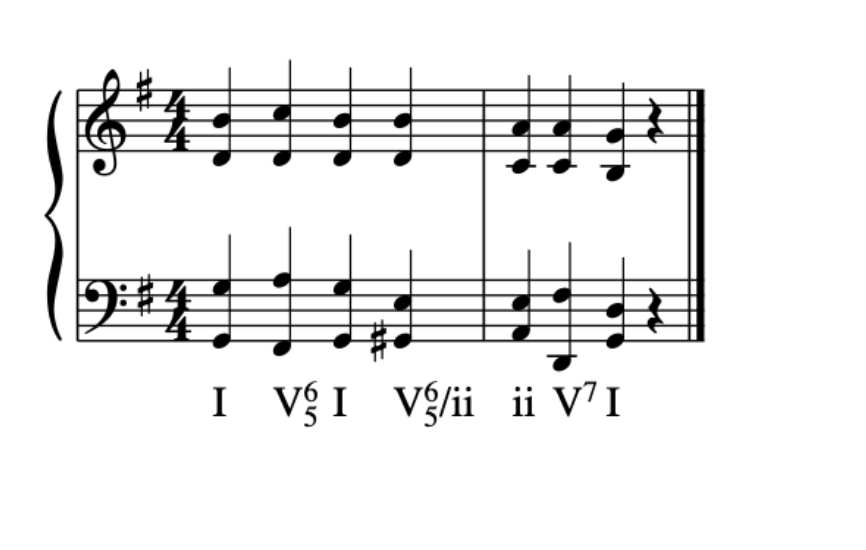

Let's look at an example, a past exam question from 2018.

Image via College Board

Let's quickly fill in the first three beats of measure 1. If you need help with voice-leading, check out these guides.

Let's now look at the V⁶₅/ii chord. In the key of G, ii is a, and the dominant of a is E. So, our chord will be E-G#-B-D#, with G# in the bass.

That will resolve to ii, which is A-C-E-G. Notice the chromatic bassline: G-G#-A.

7.3: Tonicization through Secondary Leading Tone Chords

Remember from previous lessons that the vii० has a very similar function to the V chord: they both serve a dominant function that creates a cadence when resolved to the I chord. So, just like V chords, it is useful to use a secondary leading tone during tonicization. These chords usually appear as seventh chords: vii०⁷ and viiø⁷. Note that in a major key, you can use both vii०⁷ and viiø⁷, but in minor keys, you should only use vii०⁷. Usually, fully diminished seventh chords are more common.

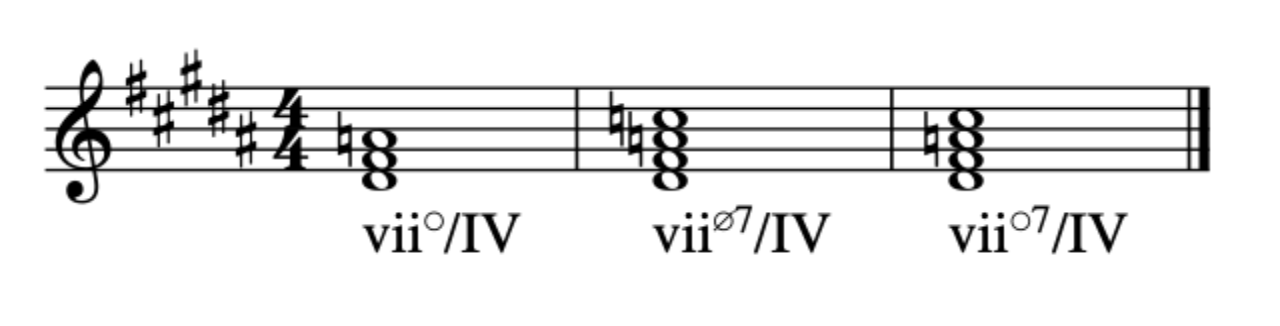

Example: Write vii०/IV, vii०⁷/IV, and viiø⁷/IV in B major.

In B major, the root of the IV chord is E, so our new tonic is E. That means that our new leading tone is D#. So, vii०/IV is D#-F#-A♮, vii०⁷/IV is D#-F#-A♮-C♮, and viiø⁷/IV is D#-F#-A♮-C#.

How do I know if I am looking at a secondary leading-tone chord?

- Start by looking for accidentals. If you see any accidentals, you should consider that you're looking at a secondary dominant.

- Is it a diminished or half-diminished chord? Here's a little secret: College Board only tests on secondary dominants and secondary leading tone chords. V chords are (almost) always major, so if you're looking at a diminished/half-diminished chord with accidentals, then you're looking at a secondary leading-tone chord.

Let's look at another example. Try to analyze the chords in Brahms' Intermezzo, op 119 no. 3 in C major

Image via Wikipedia

Start by looking at measure 1 of the excerpt. On beat 1, the bass clef has a broken G major triad, and the treble clef has an F. (C is a passing tone) So, beat 1 is a V⁷ chord. On beat 2, there is a I⁶₄ chord, which is a passing 6-4 chord.

In measure 2, we have something interesting. On beat 1, we have a ii०⁶₅ chord (F-Ab-D-C), and on beat 2, we have F#-A-C-E, which is a diminished 7th chord. Since there are accidentals, we know that we might be dealing with a secondary leading-tone chord. F# is the leading tone for G, which is V of C, so we can write the chord in beat two as vii०⁷/V.

Why didn't we analyze beat one as a secondary leading tone? The notes on beat one are F-Ab-D-C, which means that the secondary leading tone would be in an inversion: we would write it as a 6-5 chord. And, since D is the leading tone of E, we could write it as a vii०⁶₅/iii. However, there are two problems with this. First, we usually don't see secondary leading tone chords in inversions because it erases the dominant function of the chord. Second, musical context is important. If this were a tonicization, we would expect it to resolve to a iii triad. However, we "change key" again in beat 2 of the measure. That means that the chord doesn't serve a function as a chord in a secondary key, so we wouldn't analyze it as such.

Finally, in measure 3, we see another V⁷ chord, which makes sense musically because a vii०⁷/V is resolving to a V⁷. The last beat is another passing 6-4 chord.

Image via Wikipedia

7.4: Part-Writing of Secondary Leading Tone Chords

With secondary leading-tone chords, it's important to follow all voice-leading rules that you have learned in previous chapters. Keep in mind that, in tonicization, you'll have a different temporary leading tone, chordal seventh, and tonic. So, if we are in C major, the chordal seventh won't necessarily be F—it will be the 4th scale degree in whatever our temporary key is.

There are a few extra considerations to keep in mind when part-writing with secondary leading tone chords.

- First, you can't have a half-diminished 7th chord in minor because, in a minor key, we want to raise the leading tone to emphasize the dominant function of the vii°.

- Second, in minor keys, we don't build vii°/III or viiø⁷/III because these sound the same as ii° and iiø⁷. We also don't have viiø⁷/V, because then, we would have to both raise and not raise the leading tone in the same chord, which doesn't work.

Browse Study Guides By Unit

🎵Unit 1 – Music Fundamentals I (Pitch, Major Scales and Key Signatures, Rhythm, Meter, and Expressive Elements)

🎶Unit 2 – Music Fundamentals II (Minor Scales and Key Signatures, Melody, Timbre, and Texture)

🎻Unit 3 – Music Fundamentals III (Triads and Seventh Chords)

🎹Unit 4 – Harmony and Voice Leading I (Chord Function, Cadence, and Phrase)

🎸Unit 5: Harmony and Voice Leading II: Chord Progressions and Predominant Function

🎺Unit 6 – Harmony and Voice Leading III (Embellishments, Motives, and Melodic Devices)

🎤Unit 7 – Harmony and Voice Leading IV (Secondary Function)

🎷Unit 8 – Modes & Form

🧐Exam Skills

📚Study Tools

Fiveable

Resources

© 2025 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.