Robby May

Ashley Rossi

AP US History 🇺🇸

454 resourcesSee Units

Railroads and Cornelius Vanderbilt

After the Civil War, railroad mileage increased more than fivefold in a 25 year period (from 35,000 miles in 1865 to 193,000 miles in 1900). Railroads created a market for goods that was national in scale, and by so doing encouraged mass production, mass consumption and economic specialization.

Airbrakes, refrigerator cars, dining cars, heated cars and electric switches all transformed the business. George Pullman’s lavish sleeping cars became popular.

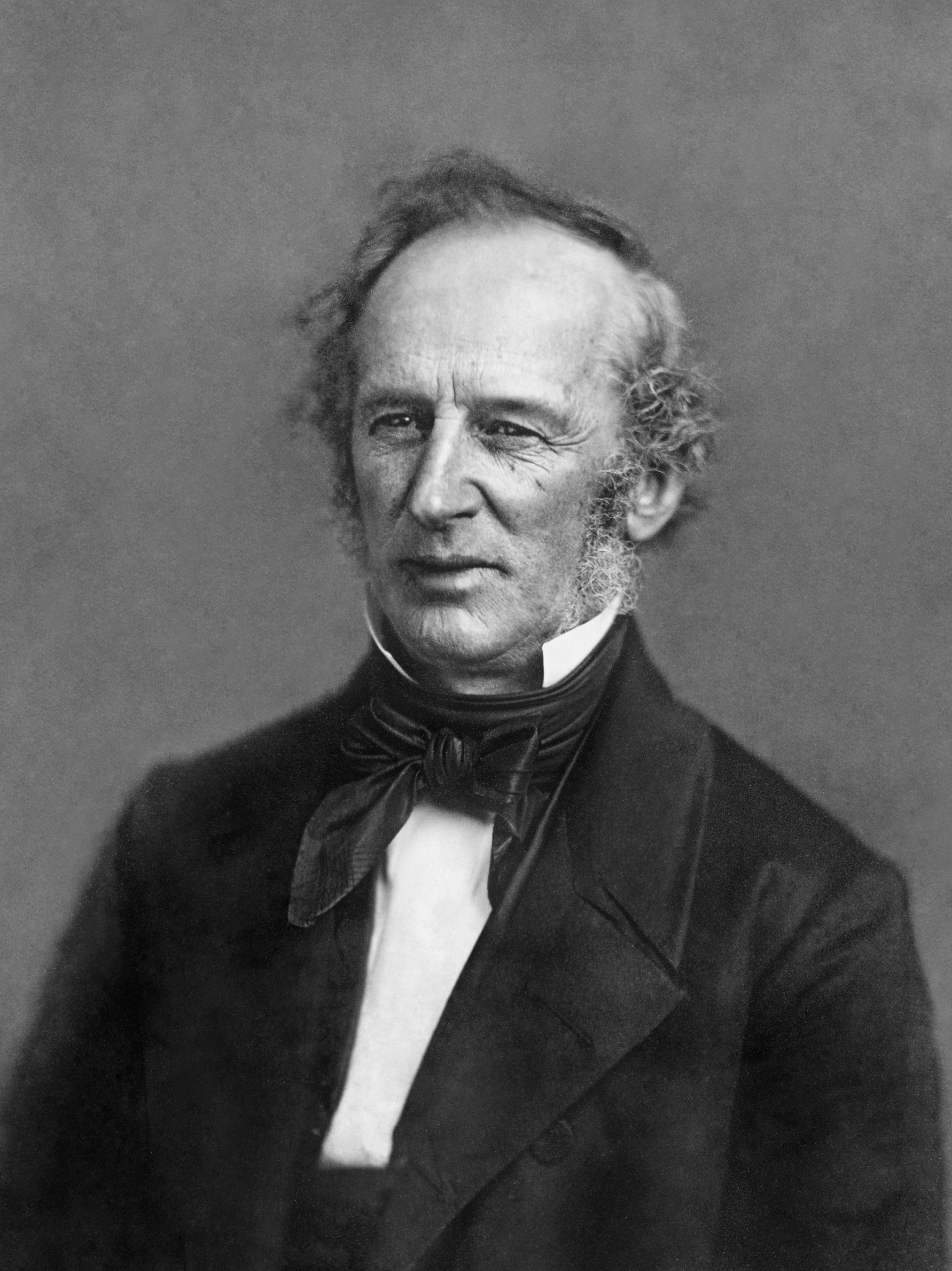

Image Courtesy of Wikimedia

“Commodore” Cornelius Vanderbilt used his millions earned from the steamboat business to merge local railroads into the New York Central Railroad, which ran from NYC to Chicago and operated more than 4,500 miles of track.

Recognizing that western railroads would lead the way to settlement, the federal government provided railroad companies with huge subsidies, in the form of loans and land grants. The government gave 80 railroad companies more than 170 million acres of public land. It was given in alternate mile-square section in a checkerboard pattern along the proposed route of the railroad.

During speculative bubbles, investors often overbuild new technologies as did railroad owners. Railroads also suffered from mismanagement and outright fraud. Speculators such as Jay Gould entered the railroad business for quick profits and made their millions by selling off assets and watering stock (inflating the value of a corporation's assets and profits before selling its stock to the public).

To survive, railroads competed by offering rebates (discounts) and kickbacks to favored shippers while charging exorbitant freight rates to smaller customers such as farmers.

A financial panic in 1893 forced a quarter of all railroads into bankruptcy. J. Pierpont Morgan and other bankers quickly moved in to take control of the bankrupt railroads and consolidate them.

Steel and Carnegie

In the 1850s, both Henry Bessemer in England and William Kelly in the US discovered that blasting air through molten iron produced high-quality steel (a more durable metal than iron).

Andrew Carnegie was the undisputed master of the industry. South of Pittsburgh, he built the J. Edgar Thomson Steel Works, named after the president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, who was his biggest customer. In 1878 he won the steel contract for the Brooklyn Bridge. He also would provide the steel for NYC’s elevated railways and skyscrapers and the Washington Monument.

In 1901 he sold the company believing that wealth brought social obligations and he wanted to devote his life to philanthropy. JP Morgan bought it as he was Carnegie's chief competition in the Federal Steel company. Carnegie sold it for a half billion dollars. Drawing other companies into the combination in 1901, Morgan announced the creation of the US Steel Corporation.

Rockefeller and the Oil

In the 1850s, petroleum was a bothersome, smelly fluid that occasionally rose to the surface of springs and streams. Some entrepreneurs bottled it in patent medications and others burned it. Soon it was discovered that by drilling, you could reach pockets of it under the earth. John D. Rockefeller imposed order on the industry.

Rockefeller absorbed or destroyed competitors in Cleveland and elsewhere. Unlike Carnegie, he was distant. He had deep religious beliefs and taught Bible classes.

He demanded efficiency and relentless cost cutting. He counted the stoppers in barrels, shortened barrel hoops to save metal, and reduced the number of drops of solder on kerosene cans from 40 to 39. He realized that even small reductions meant huge savings. By 1879, through his company, Standard Oil, he controlled 90% of the country’s entire oil-refining capacity.

Some people at the time viewed these men as corrupt and harmful robber barons 🤑 while others saw them as brilliant and innovative captains of industry. Which is closer to the truth? Well, that’s for you to argue.

🎥 Watch: AP US History - Period 6 Review

New Business Organization

Business leaders used new tactics to consolidate wealth and drive out competition.

Explanation | |

Vertical Integration | company would control every stage of the industrial process, from mining the raw materials to transporting the finished product. |

Horizontal Integration | integration of an industry, in which former competitors were brought under a single corporate umbrella |

Trusts | A board of trustees controls and manages all of the different companies for an organization instead of each company having its own board of trustees to run it. Basically, this is a horizontal organization with trustees. |

Holding Companies | A holding company is a company that owns the outstanding stock of other companies. A holding company usually does not produce goods or services itself. Its purpose is to own shares of other companies to form a corporate group |

Capitalism

As early as 1776, economist Adam Smith had argued in The Wealth of Nations that business should be regulated, not by government, but by the “invisible hand” of the law of supply and demand. If the government kept its hands off (laissez-faire), so the theory went, businesses would be motivated by their own self-interest to offer improved goods and services at low prices.

Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection in biology presented new views of economics for some. Some people argued that Social Darwinism, the belief that Darwin’s ideas of natural selection and survival of the fittest, should be applied to the marketplace. They believed that concentrating wealth in the hands of the “fit” benefited everyone.

Gospel of Wealth

A number of Americans found religion more convincing that Social Darwinism in justifying the wealth of successful industrialists and bankers. Because he diligently applied his Protestant work ethic to both his business and personal life, John D. Rockefeller concluded that “God gave me my riches.”

Andrew Carnegie's article “Wealth” argued that the wealthy had a God-given responsibility to carry out projects of civic philanthropy for the benefit of society, the idea of the Gospel of Wealth. He himself distributed more than $350 million of his fortune to support the building of libraries, universities and various public institutions.

Browse Study Guides By Unit

🌽Unit 1 – Interactions North America, 1491-1607

🦃Unit 2 – Colonial Society, 1607-1754

🔫Unit 3 – Conflict & American Independence, 1754-1800

🐎Unit 4 – American Expansion, 1800-1848

💣Unit 5 – Civil War & Reconstruction, 1848-1877

🚂Unit 6 – Industrialization & the Gilded Age, 1865-1898

🌎Unit 7 – Conflict in the Early 20th Century, 1890-1945

🥶Unit 8 – The Postwar Period & Cold War, 1945-1980

📲Unit 9 – Entering Into the 21st Century, 1980-Present

🚀Thematic Guides

🧐Multiple Choice Questions (MCQ)

📋Short Answer Questions (SAQ)

📝Long Essay Questions (LEQ)

📑Document Based Questions (DBQ)

📆Big Reviews: Finals & Exam Prep

✍️Exam Skills (MC, SAQ, LEQ, DBQ)

Fiveable

Resources

© 2023 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.